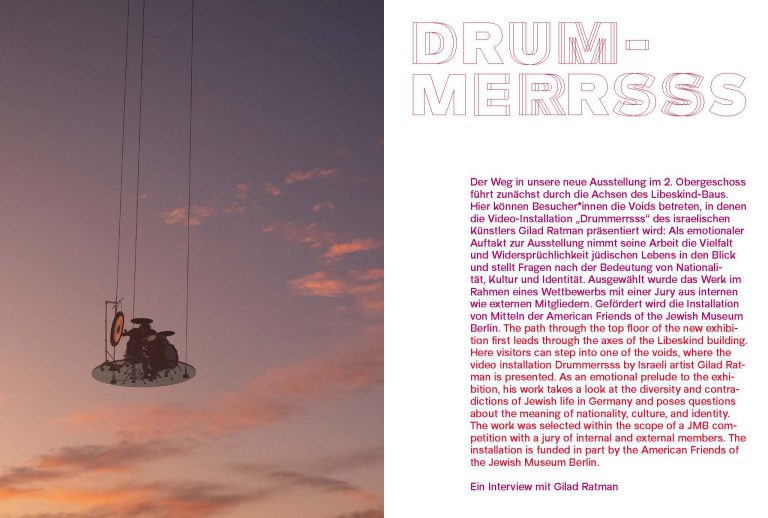

The path through the top floor of the new exhibition first leads through the axes of the Libeskind building. Here visitors can step into one of the voids, where the video installation Drummerrsss by Israeli artist Gilad Ratman is presented. As an emotional prelude to the exhibition, his work takes a look at the diversity and contradictions of Jewish life in Germany and poses questions about the meaning of nationality, culture, and identity. The work was selected within the scope of a JMB competition with a jury of internal and external members. The installation is funded in part by the American Friends of the Jewish Museum Berlin.

An interview with Gilad Ratman for the Jewish Museum Berlin.

Your impressive video-installation Drummerrsss can be seen within one of the voids of the Libeskind building; it is one of the first exhibits our visitors will encounter. At first glance, it doesn’t necessarily show any specifically Jewish aspects. So my question is: How does this work of art relate to a Jewish Museum?

GR: My idea was that the museum has a historical but also a thematic perspective. My first decision was not to follow history, not to follow events, but to approach the themes. The theme that I understand as the core of this museum is the question of identity. It’s a question of coexistence, not the coexistence of different nations, but the coexistence within a person: “What is it to be German and Jewish?” Which by the way is not completely different from asking “What is it to be a Moroccan and Jewish?” or “What does it mean to be German?” It’s a conflict. Identity is formed by many things, but two elements are the very dominant: One is nationality, which is very much tied to land, to territory and borders, and the other is a set of beliefs, a spirituality or ideology, which is something that guides you in life, but which is not necessarily connected to where you live. The difference of these two elements creates friction. How do they coexist? How do they touch each other? Intuitively I chose drumming as the main theme of my work, because there is something in drumming that combines both: Drumming stems from a specific culture and it is related directly to the body, related to life and death. To be alive means to have a heartbeat inside of you. To have a pulse. That’s why I chose drumming, two drummers; one a few meters in the ground, and the other right above him. A man and a woman. Both drummers relate to each other on a vertical scale, and this is very important. It’s happening simultaneously. The drummers’ connection is both in and out of sync. Being synced or out of sync doesn’t necessarily translate to good and bad. It is how we relate to our existence. Sometimes your nationality and your set of beliefs are synched and maybe that means they are stable: not necessarily good, but stable. If they are not synched—unstable, shaky—that is not necessarily bad. The relation between those two elements can be very fruitful; it can be what we actually want in our world. We don’t want identities to be monolithic. But conflict can also lead to disaster, as we already know.

You picked a very specific landscape in Germany for your work. Why this one?

GR: This wasn’t something I planned in advance. I was looking for a landscape that would speak to me in some way, and serendipitously, we had the opportunity to go to Saarland. There, I understood that the landscapes where actually former quarries. This knowledge— even though it’s not up front—adds another layer to my work because of the miners’ physical and emotional relationship to the ground itself: What they actually do is hit the ground, not unlike drummers hitting their drums. In this work we translate their physical activity into something that is musical. Another aspect of this specific landscape is that one cannot really identify it as a typical German landscape. This could be Germany or Israel; it could be anywhere. This, in my opinion, is the lesson from the disaster that happened here. It is related to human race. In no way do I think that one can understand it by looking at German history alone. Opportunity creates evil, this is my opinion. We can see evil everywhere. I didn’t need to show a very German context, because what surrounds the work, surrounds myself as a visitor and viewer is part of the work’s content. And because it is in the Jewish Museum, in Berlin, within this very heavy context, I can do less. I don’t need to represent everything. Yes, this work could travel to different museums, but once it is right here, it absorbs the context of its surrounding.

How does your work relate to the architecture by Daniel Libeskind? He designed this museum with National Socialism and the Holocaust in mind.

GR: Oh, of course, I meant to mention this earlier. My work relates first of all to his specific architecture. If you ask, “What is in this film?” it is exactly what the architecture is doing: being underground, looking to the sky. It is a very existential experience. It hits you with life-death-identity, and one has to work with it and find what one can do with it.

So for you, a work of art corresponds with the place one sees it? That also means it doesn’t create the same meaning everywhere.

GR: Yes! Museums such as art museums function as something that is kind of neutral. But usually art museums try to be neutral: this is art, this is the white cube. But once you show a work of art in a context that is not neutral, art becomes something else. If I do a piece for the Knesset in Israel it has to engage with that. So when I’m doing a piece for the Jewish Museum Berlin, there’s a lot of heavy context. Actually the heaviest context I have ever allowed myself to deal with. Situated here, I believe that a work of art should be independent in a way that doesn’t provide or echo the context that is here, but which makes it able to absorb, to reflect, to raise more questions. People will come and see many things within this work: The Holocaust and then the hole in the ground; perhaps they will say “your brother’s voices are screaming from the ground.” Or they will say “This is Babi Jar.” They could say, they see Jewish kabbalah, the sefirot, shamayim va-aretz in this work. Visitors will see and say many things. And, yes, I have to take responsibility for what they see.

Bringing this work to life was an adventurous plan: Could you give us a little bit of insight into the making of? What did you and your team experience on set?

GR: The project was an adventure: Understanding the unique terrain of the mining site, working closely with four engineers in order to dig the hole and to hang the drummer on the glass surface. We learned about digging techniques from the experience and the expertise of the miners who used them for many years. But, our biggest challenge was the “flying” drummer: Alex never had a similar experience in her life. She had never hung in the air while drumming… We had no option to rehearse this. But Alex was just amazing. She was drumming in the air like she was born there. We had may visitors on set. I think they will all remember that moment when a crane lifted the glass stage with the drummer and carried it to the sky. When the two drummers played together, it sounded like a concert. One that we have never seen before. It was thrilling.

You are Israeli; what did that add to the idea of your piece? What is your perception of the relationship between Israelis and Germans?

GR: I have many opinions on this, but I don’t think the piece can say all this. A piece of art cannot cover everything! It needs to take something and go with it. What I would like, is this piece to be the starting point of a discussion about identity—in any country.

Sunday

Monday

Tue – Thu

Friday

Saturday

Closed

By appointment only

11:00 – 18:00

11:00 – 14:00

11:00 – 14:00

Design by The-Studio

Code By Haker Design